Data can unlock many opportunities in care & healthcare, but this depends on providers taking charge of data in their technology stacks.

by Paul Tomlinson, 6th December 2023

Care & healthcare providers have different priorities related to data, mostly related to the scale of their organisations.

- At providers of adult social care, such as care agencies and care homes, data is most often discussed regarding compliance, and the protection of peoples’ secure information.

- In hospitals and at governmental / regulatory level, the discussion is more likely to be about using data to drive down costs, reducing mistakes, and improving service delivery. These conversations are now increasingly likely to mention data analytics and AI.

Of course, all of these priorities can apply to every type of care and healthcare provider. And it is now eminently possible for care agencies and care homes to reduce operational costs, and improve outcomes, through better management of data in their organisations.

This article explains the that providers should start taking now, with their data, to set themselves on the right path.

We’ll start by explain the core obstacles to effective data management and innovation in care and healthcare. There is wide variation, but broadly, these industries are characterised by legacy technology platforms, which make it very difficult to use data beyond the uses originally intended (in some cases 20+ years ago) by the technology vendor.

Next, we’ll make the case that care providers themselves must be the drivers of change. A lot of healthcare innovation is government- or regulator-led – and though these pressures are welcome, they are somewhat misaligned with what care providers most urgently need. This is because governments and care providers work to different KPIs: governments seeking to reduce costs over decades, and care providers seeking to innovate and improve patient outcomes today.

Finally, we’ll set out how care providers can proceed, by prioritising the adoption of tools specifically designed to enhance care providers’ abilities to capture, manage and share data.

Some of this will happen naturally, as care providers accept government incentives and fall in line with evolving standards – but that will be far from ‘job done’.

In healthcare as in any industry, data can unlock a very wide range of opportunities and resolve a wide range of problems. Nobody can unlock these opportunities better than the care provider themselves – but that depends on thinking proactively about data in their organisations, and the tools which impact on how that data is used.

Outdated technology is hindering the use of data in healthcare

If you follow the news in healthcare, rarely a week goes by without reading about a data incident taking place at a care or healthcare organisation.

It is not my intention to criticise the industry – but it’s important to understand the underlying causes of the problems.

In the UK in September, Newcastle hospitals lost 24,000 letters following a technology upgrade, which led to letters being “placed into a folder few staff knew existed” and remaining unsent.

In a comparable incident in the US last year, a hospital recorded “nearly 150 cases of patient harm” following a switch to Oracle’s Cerner EHR – also caused by communications inadvertently being sent to an undetectable file location.

And at Total Care Manager, we’re currently speaking to one care agency, and one care home, where data is being lost following bungled attempts to tailor legacy EHR solutions to their needs.

Technology vendors shoulder some of the blame for these mishaps – but it’s also fair to say that care providers are now stretching these legacy technology platforms beyond their intended use.

As providers have sought to replace very complicated technology, or to customise very old technology, they’ve become exposed to the limitations of these platforms, and their outdated protocols for sharing and managing data.

To understand where data typically resides in care and healthcare…

- at a care agency, care home, GP office, physiotherapy centre, etc., a typical setup would be a single, central platform such as an EHR or EPR. This software would in many cases be designed to avoid the need for any additional software, by carrying out a wide range of functions at a basic level – such as rostering, risk assessments, etc. But larger providers may still have one or two additional tools for those needs.

- at a hospital, the central data store is either a physical server room (‘on-prem’), or in cloud-based storage provided by the EPR (electronic patient record) vendor. This serves as the central database for the whole hospital, and it exchanges data with at least some of the hospital’s various tools – such as the emergency medicine system (EMS), radiography systems, and many other pieces of software.

Beyond this, however, is a picture of very significant complexity.

Across all levels of healthcare and care, it’s common to find many additional data silos, comprising written notes, flat Excel & Word files.

If the care provider uses multiple pieces of software (i.e., an EHR, a CRM, and a workforce management tool for rostering), the systems may exchange data via APIs to reduce duplication. Often, however, professionals are forced to enter and delete the same data multiple times in multiple systems – which eats up staff hours, and inevitably increases the risk of errors.

A further problem is that care providers’ technology systems are often ‘walled gardens’ – where data cannot move easily in or out of the organisation.

A doctor we spoke to at a UK hospital, using the Epic EPR, says that if a patient comes from their sister hospital – under the same NHS trust, and also using Epic – they will not be able to access the patient data. Instead, the medical professional sees an icon indicating that they can phone the sister hospital for information.

If the patient comes from any other healthcare organisation, or any other NHS trust, there may be some information available on NHS Spine – but this data is patchy (more or this below). Very often, there’ll be nothing.

*

The fragmented state of data in care and healthcare has persisted for various reasons.

The overdependency on legacy databases in hospitals – whether the hospital server room, or the main EPR vendor’s cloud storage – is perceived as being the most secure setup for individual healthcare providers.

That isn’t necessarily true; many highly secure databases are decentralised. For example, many banks, including HSBC, use Amazon Web Services for cloud data storage.

More to the point, though, walled gardens around healthcare databases are incompatible with the reality of healthcare: where patients come and go between many different care providers, and rely on those care providers to share their information effectively.

No individual EHR or EPR vendor is going to volunteer complete responsibility for this level of complexity; nor would that even be feasible, as many of these data sources are out of their control.

The only entity that can feasibly drive change here, therefore, is the care provider themselves.

Failing to lead on this change will not only leave the provider exposed to data incidents; it will also continue frustrate efforts to make use of that data – to improve patient outcomes, resolve inefficiencies, and harness AI as the technology evolves.

Care providers themselves must drive digital transformation

To date, a lot of healthcare data initiatives have been government-led. These include:

- nationalised databases

- interoperability standards

- …and funding digitalisation.

All of these initiatives are welcome, but as we explain here, they are of limited utility, unless care providers independently take steps to improve they way they store, manage and share data.

1. Nationalised health databases

One frequently-vaunted idea is idea of a nationalised healthcare data repository. The idea is that when a patient arrives at a care or healthcare provider they haven’t previously visited, their centralised patient record is readily available to the professional treating them.

The UK’s most significant effort to this end is NHS Spine, launched in 2014 and joining together “…over 44,000 healthcare IT systems in 26,000 organisations”.

This sounds impressive, until you consider that the UK has over 36,000 GPs, over 25,000 care agencies and care homes, and many thousands more dentists, opticians, physiotherapists, occupational therapists, psychotherapists, etc.

The truth is that many providers simply don’t share patient data with Spine, often because they don’t see the value, and sometimes because they themselves are not keeping digital records.

The consequence is that when a healthcare professional consults the Spine database regarding a new patient, they have no idea what may be missing from the record. In many cases, there’ll be no data on the patient at all.

Alex Lennox-Miller, a healthcare analyst at CB Insights, says that the same issues have frustrated similar efforts in the USA. Health Information Exchanges (HIEs) are centralised databases that providers subscribe to in order to purchase patient data.

Lennox-Miller explains that American care providers using HIEs faced the very same problem that UK providers experienced with NHS Spine.

“How do you create a sufficiently complete medical record, if you don’t know who is not contributing to it?

You can’t know that the patient didn’t go to an emergency room two weeks ago and get a prescription. You can’t know that the patient didn’t go to an outside specialist.

And so, it really was not useful… It was usable; it just wasn’t practicable.”

It’s important to note that hardly anybody (except governments and researchers) actually needs a giant, nationalised database.

What patients genuinely do need is for data to be appropriately shared between the care and healthcare services that they encounter in their everyday lives, and deployed at the point of need.

2. Data interoperability standards

To this end, governments have made positive steps by helping to standardise the way that data is stored, so that it can be of greater use when care providers share it between themselves.

This began decades ago in the USA with the HIPAA Act 1996, which set out data interoperability standards, and the HITECH Act 2017 (which incentivised electronic record-keeping). In the UK, providers of adult social care are now quickly implementing solutions from a government-approved Assured Suppliers List – which stipulates data interoperability standards for approved solution vendors. Both markets work to a standard known as FHIR, although this is yet to become mandatory in the UK.

Unfortunately, these standards are not as comprehensive as one might hope. Nor do they address care providers’ lingering reliance on paper and data silos, and the fragmented state of the market for which these standards are intended.

To understand these challenges, consider how healthcare is organised.

In the UK, publicly-funded care is organised by Integrated Care Systems (ICSs) –groups of local healthcare providers with responsibility for local populations of averaging 1.5m people. ICCs are supposed to… “bring together NHS bodies, local authorities and charities to plan and deliver health and care services in a more joined-up way.”

In May this year, however, The Economist reported:

“Less than half of ICSs have a data platform to help them manage their populations’ health. Privacy concerns and bungled implementation have impeded efforts to join up patient records.”

And in the US, Dr. Alan Stein – who trained as a physician, and now works for HP Healthcare Analytics – estimated in 2020 that since providers’ data is unstructured (i.e. written notes), there is widespread failure “to analyze up to 90% of their information”.

Outside of hospitals: the market for care agencies and care homes, GPs, physiotherapists, etc. is hugely fragmented, comprising many private businesses with very little coordination between them.

Even in a hypothetical situation where every care provider operates to a single data management standard, there simply isn’t the coordination or integration between providers needed to enable much useful collaboration.

3. Funding technology adoption

As mentioned, the UK’s Assured Suppliers List, and the HITECH Act in the USA, have both funded technology adoption for care providers.

This is valuable; after all, digital transformation requires funding, and any organisation – whether or not in healthcare – often needs a nudge to break legacy practices.

However, there are lessons to be learned from the way this played out in the US market, where in some ways, government pressure actually further complicated data interoperability between care providers.

Lennox-Miller explains that, under HITECH, vendors…

“…had to have certain features and meet certain standards in order to be a certified EHR -and then you were eligible for all this reimbursement and subsidies.

The result was a hugely fragmented EHR market. And because a lot of those requirements didn’t include standards for data interoperability, data management and data sharing, it became a huge problem for US data infrastructure about 10 years.”

As to the UK market: based on our conversations at Total Care Manager, we can report that the two EHR vendors that we know to be losing their clients’ data are both certified by NHS Digital’s Assured Suppliers List.

As a regulator or a government, you can throw as much money at technology adoption as you want. Unless care and healthcare providers are educated in the factors that hinder and enable the use of data – and believe that this is important – the entire industry’s capabilities around data will continue to lag behind.

Prioritising data agility in your healthcare technical architecture

The most interesting case studies on the use of healthcare data are not, typically, national or government-led initiatives. In most cases, they are on individual care or healthcare providers, who have the autonomy to implement the technology needed to pursue this initiatives independently.

The right technology approach differs depending on your scale and your budget, so, I’ll talk first about smaller care providers such as care homes and care agencies, and then about hospitals.

In all cases, though, the priority should be to select technology which assists in the movement and management of data in the organisation, and between connected systems.

Generally, this implies selecting and implementing ‘API-first’ software. An API-first software platform is one designed in anticipation of the need to share data with other software components. Learn more in our previous article on composable care technology here.

For care agencies, residential homes and other smaller care providers

A key objective for care businesses should be to automate the flow of data – rather than keeping multiple data silos, or manually inputting the same data multiple times into different systems.

This is important for 3 reasons:

- saving significant operational costs. The costs of maintaining data silos, and manually moving data around the business, can have a massive impact on your budgets. If you have one manager spending 8 hours a week transferring data from one system to the next, that likely costs you £10,000 a year. Any many care providers the total figure could be several times that.

- the inherent associated risks of legacy practices – such as paper records being lost, or flat files such as Excel documents being accidentally deleted, corrupted or stored insecurely

- the opportunity to make important business and operations improvements, including in the improvement of patient safety and patient care.

Regarding operational costs: where systems are not integrated, care providers very often rely manual labour to move data from one system to another.

For a common example, consider payroll and rostering systems – which are often two different pieces of software.

In the optimal setup, the rostering system simply passes through the record of completed shifts into the payroll software – which then generates automated timesheets and payslips. Nearly all of this process could be automated, with some manual oversight for irregularities and corrections.

Yet at many care businesses, manual timesheets are still commonplace. That could be because that’s how they’ve always done things – or, because the bundled care-and-rostering system was simply never designed to connect to payroll software.

A care provider’s existing technology could, in theory, be customised with such an integration, but that may incur prohibitively a high cost. There would also be a high risk of unexpected mishaps – as per the Oracle Cerner example above, and as it often the case when you try to customise legacy software.

As a result, the manual management of data persists very widely in the care sector – to the cost of hundreds or even thousands of wasted staff hours per year, even at fairly small companies.

As to the risks of keeping paper records and flat files: a piece of 2016 research by the CQC (Care Quality Commission) research estimated that 80-90% of data breaches were a result of ‘human behaviour’ – including accidentally losing storage devices, paper notes being lost, or emails sent to the wrong people.

Furthermore, storing data in this way leaves businesses vulnerable to criminals. In 2022, a domiciliary care service in Liverpool fell victim to a phishing scam whereby the attacker gained access to the carers’ personal devices.

Of course, modern care software won’t prevent phishing scams (this is more to do with email security). But where an organisation uses modern software, access to systems and the transfer of data is more likely to be restricted by modern protocols – since those tools were designed and built in the age of cybercrime. By contrast, many commonplace tools used in the care sector are 20-30 years old, and have little to no inbuilt security.

Finally, the ability to make improvements in care and operations based on data.

This anecdote from Liam Palmer, a care entrepreneur who previously worked as a care home manager, is a classic example of how effective data management can improve on patient outcomes (hear the full interview with Liam here).

Whether or not this resident’s meals, or weight, were being recorded was not the issue here; it was whether that data was accessible at the point of need.

In this case, the ‘point of need’ was the care manager, the wider care team, and whatever systems they were using to exchange information from carer to career, shift to shift. But there could be many points of need.

These could include the care provider’s compliance, risk assessment & HR systems – where incidents are tracked and reported, so they can be analysed and reduced in the future. It could be the patient’s hospital passport, or the systems used by their hospital, GP, or other healthcare providers, so that this change in the patient’s condition & associated notes were available to all relevant professionals.

For hospitals and other large providers

The improvements described above are also applicable to hospitals – which also still suffer from a lot of data duplication and manual processes.

Hospitals, however, are interesting because they operate at such a scale where data analytics becomes practically useful – which opens the door to the industrial-scale use of AI.

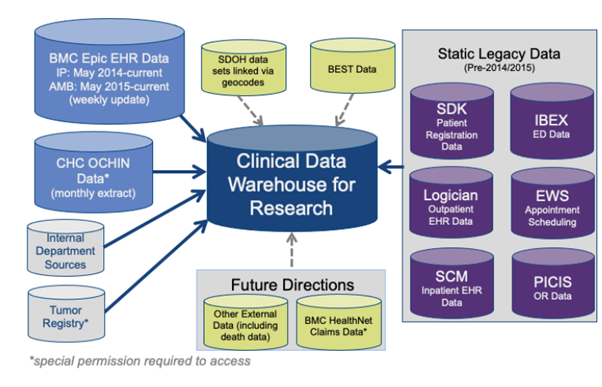

A widely-recognised leader in the field of healthcare data is Boston Medical Centre. Boston is a small hospital widely acknowledged as a technology leader, and it published this diagram showing the various elements in its data stack.

To many healthcare professionals, this diagram may appear confusing, but actually, it’s quite easy to understand with a bit of explanation.

At the top left is the Epic EHR – the most commonly used piece of software used in hospitals and the wider care industry. You may be familiar with other EHR solutions, including Oracle Cerner, and comparable tools used for domiciliary care and nursing homes (such as Nourish Care, Birdie, and Total Care Manager).

Scattered around the diagram are other pieces of software, and other data silos – which Boston hospital has successfully digitalised, so that they can be absorbed into the data warehouse.

The data warehouse – the blue module in the middle- is essentially a database, with advanced functionality for data analytics. It is now very common for large organisations of comparable size to hospitals (i.e., circa £50m+ annual expenditure or £100m+ revenue) to have a data warehouse, which pools data from across the business for ease of management, analytics, and advanced data processing, including AI.

Data warehouses do have a certain minimum viable scale, as they require significant technological expertise in-house to set up and run.

But they are invaluable to large organisations relying on legacy technology platforms, such as a central EHR, surrounded by various other pieces of software.

This is because, either by accident or by design, these systems were never originally designed to exchange data with each other. On the example of Epic, Lennox-Miller explains…

“Epic has resisted interoperability as long as they possibly can. Epic has always been incredibly proprietary about access to their data, access to their technology.

…you can say that’s because they’re really dedicated to protecting and preserving data from potentially less-developed third party applications… [or] you could say it’s because they want as closed an ecosystem as possible – one that they control.”

Indeed, the providers of legacy solutions such as Epic or Cerner (or in adult social care, Access or OneTouch) typically sought to capture most or all of a company’s budget by providing very comprehensive functionality in a single bundled solution.

Of course, integrations with these systems are possible, but subject to costly custom software developments.

By contrast: with a purpose-built, API-first database at the centre of the stack, you only need one integration between the database and each individual platform – so it’s a simpler, more rational and more agile setup.

This greatly reduces long-term costs, gives the hospital far greater control over how that data is managed, shared and analysed. It also greatly enhances capability around data analytics, because data from many systems is neatly organised in one place, making it easier to draw insights based on combining and comparing data sets.

*

The need to optimise the flow of data through care and healthcare organisations will only accelerate, as care providers look past antiquated systems, towards specialised individual tools for various parts of their business.

Some examples include Radar for compliance, various different workforce solutions (i.e. RotaCloud, Sona, Shiftbase), sound & movement monitoring (i.e. Samm.app), wearable tech, facilities management, and more.

In hospitals, meanwhile, the use of cloud-based data warehouses will become more widespread, in response to the large number of different pieces of technology needed in medical care.

Care providers will increasingly need to bring cohesion to the storage and use of data across those systems, and make use of that data in ways that they see fit.

That includes in ways that governments, regulators and the technology vendors may never have anticipated – but which may improve the care provider’s ability to drive down costs, improve safety, and deliver better-quality care.

The near future of data-enabled healthcare & care

One thing we have not discussed in much detail in this article is artificial intelligence (AI). AI is increasingly a feature of many software platforms – but for now, it has the potential to be a distraction from the challenges facing most care and healthcare organisations.

AI, essentially, is the combination of:

- data processing

- with software that makes decisions or takes actions based on that data.

To give an example of use-cases of AI in healthcare:

- an EHR with AI functionality may be able to scan a page of handwritten notes and, maybe with 60-75% accuracy, translate those notes into data. With typed text (i.e., a prescription) accuracy could be 90-100%, though it would still need some human oversight.

- a hospital or large care provider with a central database could use AI to do things like identifying patients at risk based on health observations. It could also be used to find operational efficiencies, such as making better use of the availability of beds and operating theatres, and drive down waiting times for procedures. See some examples here.

Of course, AI – like any form of data processing – can only ever be as useful as the data which supplies it. So, the first step for taking advantage of AI as the same first step for making better use of data in healthcare: getting that data organised, and exposed at the point of need.

As discussed, this is happening – gradually – through the adoption of modern technology, and the gradual spread of knowledge through the care and healthcare sectors.

But there is no reason this cannot play out more quickly. The only obstacles are the time and resources that care providers are willing to invest in driving digital transformation in their organisations – and the education piece around why investing in data capabilities is worthwhile.

The challenges facing modern healthcare – limited budgets, growing numbers of people in of care, and increasingly complex technology stacks – will only increase over the coming decade. Faced by such challenges, and with the potential to transform the industry for the better, there’s no time like the present for putting that data to work.

Learn more about data & technology in care and healthcare

Our previous article, on composable care software, describes best practices for technology buying in care. In the article, we differentiating between inflexible legacy systems, and modern tools that free up innovation, and ease control and management of data in your orgnanisation.

Total Care Manager: API-first Electronic Health Record (EHR) platform

Total Care Manager is the only EHR microservice designed for complex care and more.

As an API-first vendor, we provide the core technology modules needed for care: care management, care plans and eMARs.

Designed for complex care, we can handle any level of patient dependency and clinical need, including complex care, adult social care and more.

And as an API-first platform, we can integrate easily with your other business software, allowing data to flow between sytems with no manual processes, and no duplication. That includes generic business software, such as rostering and CRM, and other, less-specialised care management platforms.

Find out more about Total Care Manager here.